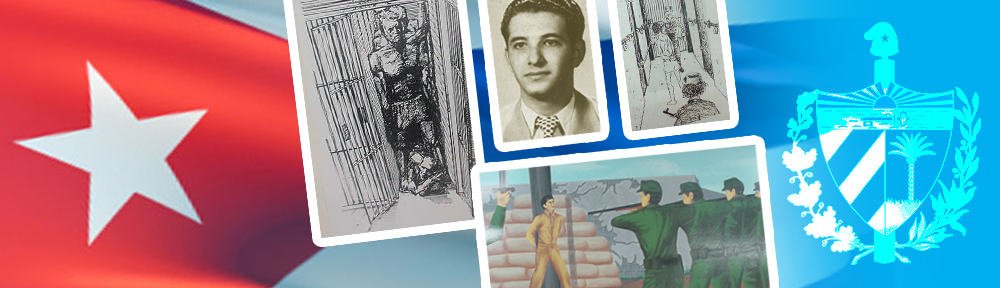

Miguel Sanchez, as a child from the age of 12 until he reached the age of 19 served as the courier or messenger to the Cuban political prisoners known as the “Plantados”.

Hidden in the collar of his shirt, inside his mouth and on occasions tucked behind his groin he smuggled out to other prisons and the outside world a large portion of what we know today as the history of the political prisoners of Cuba. During this period he was the secret courier and messenger for commander Huber Matos and the first link facilitating his organization within Cuban political prisons which later became the organization known as the C.I.D. (Cuba, Independent and Democratic)

He smuggled out a portion of Huber Matos’s book “Como Llego la Noche”, as well as numerous other works, among them Armando Valladares’s “Desde mi Silla de Ruedas,” “los Plantados” written by his father Nerin Sanchez, Eduardo de Juan’s “Jardin de Heroes”, the correspondence of Andres Vargas Gomez, grandson to the War of Independence hero Maximo Gomez. He smuggled out the list compiled by Raul Perez Coloma (El Queso) of political prisoners, both men and women identifying them by their prison ID number, their charges, and their sentence. In addition, he brought out the names of the thousands of guerrilla combatants who had perished fighting in the mountains and the cities of Cuba. He smuggled out the names of the “Plantados”, the famous letter of the 138 inmates opposed to the dialogue of 1978, and many other documents which became the primary source for a number of books, documentaries, and movies.

While still in Cuba, Miguel Sanchez would send these letters and documents to Humberto Medrano, journalist for “Diario Las Americas” who, laboring from Miami, was the first to courageously take up the cause of the Plantados.

Miguel Sanchez, as the messenger and courier for the Cuban political prisoners, was able to expose to the world and the younger generations of Cubans the horrors of Castro’s prisons and the courage of those “giants” of that era who fought for liberty from the very beginning of the revolution.

These historical documents served to prove the lie to Fidel Castro’s claim that there were no political prisoners in Cuba.